The Caste System in India: An Analysis of Its Social and Economic Impact

The Indian society has its strong background in the caste system. Indians are classified under different sections or classes due to this caste system, derived from ancient Vedic texts based on occupation or varna. After so much of cultural and civilizational growth of India, it is observed that the caste system still has dominance in Indian society, thereby providing great social and economic issues in the nation.

Origin and Development of Caste System

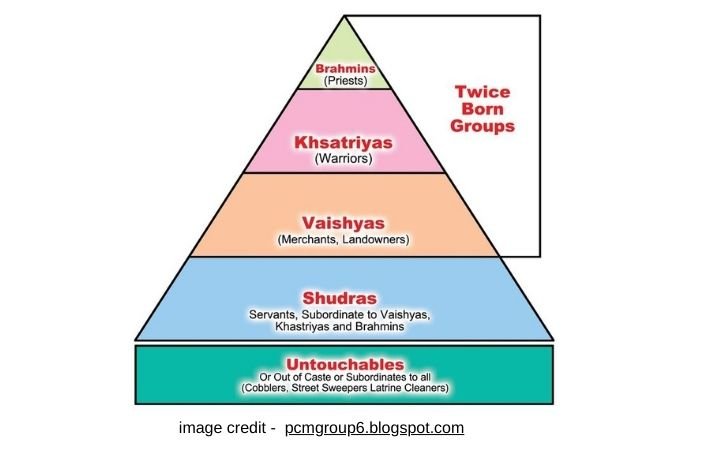

The origins of the caste system date back to the Vedic period when the varnas identified people in the society into specific roles like priests, warriors, traders, and laborers. These eventually grew into fixed hierarchies, which made it possible to differentiate between the higher and lower castes in the society. In turn, these upper castes used their social and economic superiority to take advantages over the lower castes and, hence, the existence of systemic discrimination.

One of the most marginalized populations is the SC and ST, classified historically as the “untouchables.” Some 160 million people, around one-sixth of India’s population, and continue to bear the brunt of discrimination and segregation in India today.

The Caste System’s Effect on Indian Society

Untouchability

In most villages, social and physical lines separate caste groups. Lower castes, especially SCs, are usually prohibited from crossing those lines, drawing water from the same wells, or even taking tea from the same stalls as upper castes.

Discrimination

Neighborhoods of lower castes rarely have electricity, sanitation, and water pumps. Educational facilities, housing, and health facilities are often not as good or not available as those of the higher castes.

Occupational Restrictions

Historically, lower castes were restricted to menial and stigmatized occupations: sanitation work, leatherwork, and street cleaning, among others. This form of occupational segregation perpetuates economic disparity and limits social mobility.

Exploitation and Slavery

Most lower-caste people are in some form of exploitative practice under the guise of paying off debts or serving out any form of traditional obligation. Such practices usually continue for generations, entrapping families in a cycle of debt and servitude.

Government Efforts Against Caste Inequality

Constitutional Provisions

Fundamental rights guarantee equality and prohibit untouchability. Articles 14 through 18 of the Indian Constitution guarantee the right to equality:

- Article 14: Ensures equality before the law.

- Article 15: Prohibits discrimination on the basis of religion, ethnicity, caste, sex, or place of birth.

- Article 16: Guarantees equal opportunities in public employment.

- Article 17: Abolishes untouchability.

- Article 18: Prohibits the conferment of titles.

Legal Reforms

- Untouchability was abolished in 1950.

- Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, made caste violence and discrimination a crime.

Reservation Policies

SCs, STs, and other backward classes were provided with reserved seats in educational institutions, government jobs, and legislative bodies.

Social Welfare Programs

Welfare departments and commissions were established to aid the development of SCs and STs.

These measures have somewhat eased the situation, particularly in urban regions, where social mobility and consciousness are greater. The situation in rural regions remains unchanged and continues to be marred by deep-rooted discrimination and exploitation.

Economic Costs of the Caste System

The caste system has heavy macroeconomic costs that have stalled India’s economic growth. It hinders resource allocation, dampens entrepreneurial spirits among lower castes, and perpetuates income inequality.

Differences in Firm Ownership and Productivity

The lower castes make up about 29.5% of India’s population but own less than 15% of firms. Higher-ranked castes own 70% of the capital and produce 60% of the aggregate output. Firms owned by lower-ranked castes face serious financial constraints:

- Credit Access: The lowest ranked castes account for only 4.7% of total credit. Although they are the majority, their output-to-credit ratio is twice that of the higher castes, meaning they are highly efficient in the face of low resource availability.

- Relative Productivity: The average revenue product of capital (ARPK) of the firms owned by lower castes is 25-30 percent higher than those owned by the higher castes. This indicates that lower caste entrepreneurs use capital more efficiently, but they remain constrained by the limited access to resources.

Regional Disparities

Caste-driven financial constraints are exacerbated in regions with underdeveloped financial markets. States like Bihar, Jharkhand, and Uttar Pradesh exhibit stark disparities, where lower-caste firms’ ARPK is double that of higher-caste firms. In contrast, states with better financial systems show minimal differences.

Impact on Entrepreneurship

Caste-based financial constraints hinder the entrepreneurial potential of lower-ranked caste people and steer them into low-paid labor jobs. In addition, these constraints further restrict income and wealth prospects for lower caste households, but do encourage income disparities among higher castes.

Macroeconomic Costs of Caste-Based Inequality

Studies suggest that caste-driven financial constraints decrease output per worker by 5.6%. Closing those gaps would unleash substantial economic benefits through:

- Resource Reallocation: The capital would be shifted from less productive higher-caste firms to more efficient lower-caste firms, which would increase productivity overall.

- Increased Entrepreneurship: The easing of borrowing constraints for lower-ranked castes would increase the number of people opening businesses, thereby increasing employment and economic activity.

- Improved Labor Market Outcomes: Labor markets would be more integrated as caste-based barriers break down, and the lower-ranked castes would benefit the most.

The Way Ahead

While the government has been successful in a few initiatives, equality will have to be socially brought about. Financial inclusion programs for lower-caste entrepreneurs unlock their economic potential, leading to wealth creation and poverty reduction. In addition, systemic biases need to be addressed in education, employment, and credit allocation.

Research highlights further investigations into reasons that cause financial gaps. The biggest obstacles to this objective will come from dismantling all barriers blocking lower-ranked caste individuals from having easier access to credit.

Conclusion

Deep-rooted social and economic implications of caste systems have restrained India’s overall development. There are constitutional protections and governmental interference, yet, caste-based inequality is rampant at the grassroot level. Overcoming these factors requires both change in policies as well as transformation in societal behaviors. If it can make every citizen equal with equal opportunities, then India will gain its maximum economy and create an inclusive future.